On January 20, Air Force One, a Boeing VC-25, suffered electrical issues and aborted its flight to Davos with President Donald Trump on board. It was the latest in a series of public, often catastrophic failures Boeing has suffered in recent years.

The company can trace its downward trajectory to the decrease in defense spending following the Cold War. After the company merged with McDonnell Douglas in 1997, the new executives replaced Boeing’s famously engineering-focused culture with short-term gains, cost cutting, outsourcing, and quarterly bottom lines. To the engineers who had once made Boeing a darling of U.S. aviation, the company’s troubles today are no surprise.

My own research field, particle physics, faces a similar dynamic that should serve as a warning for the future of U.S. science.

How the U.S. funds science is a big part of the problem.

Where Boeing’s executives sidelined engineers in favor of squeezing their supply chain, lawmakers’ budgetary politics over the last several decades have forced particle physicists to sideline the “dream big” mantra that once made the U.S. a scientific hegemon. Unless the Department of Energy re-establishes direct lines for scientists to provide input on research priorities, and Congress can pass bills that protect multi-year funding, the engine behind tomorrow’s innovation will fall into an irreparable decline.

Put simply, physics is having its Boeing moment.

Short-Sighted Choices

Like Boeing, physics labs in the post-war era benefited from a culture that let technical experts lead the way to prosperity. For example, some of the world’s top scientists – many of them refugees – worked on the Manhattan Project. Hungarian-born mathematician and physicist John Von Neumann envisioned modern computing; his contributions birthed the information age.

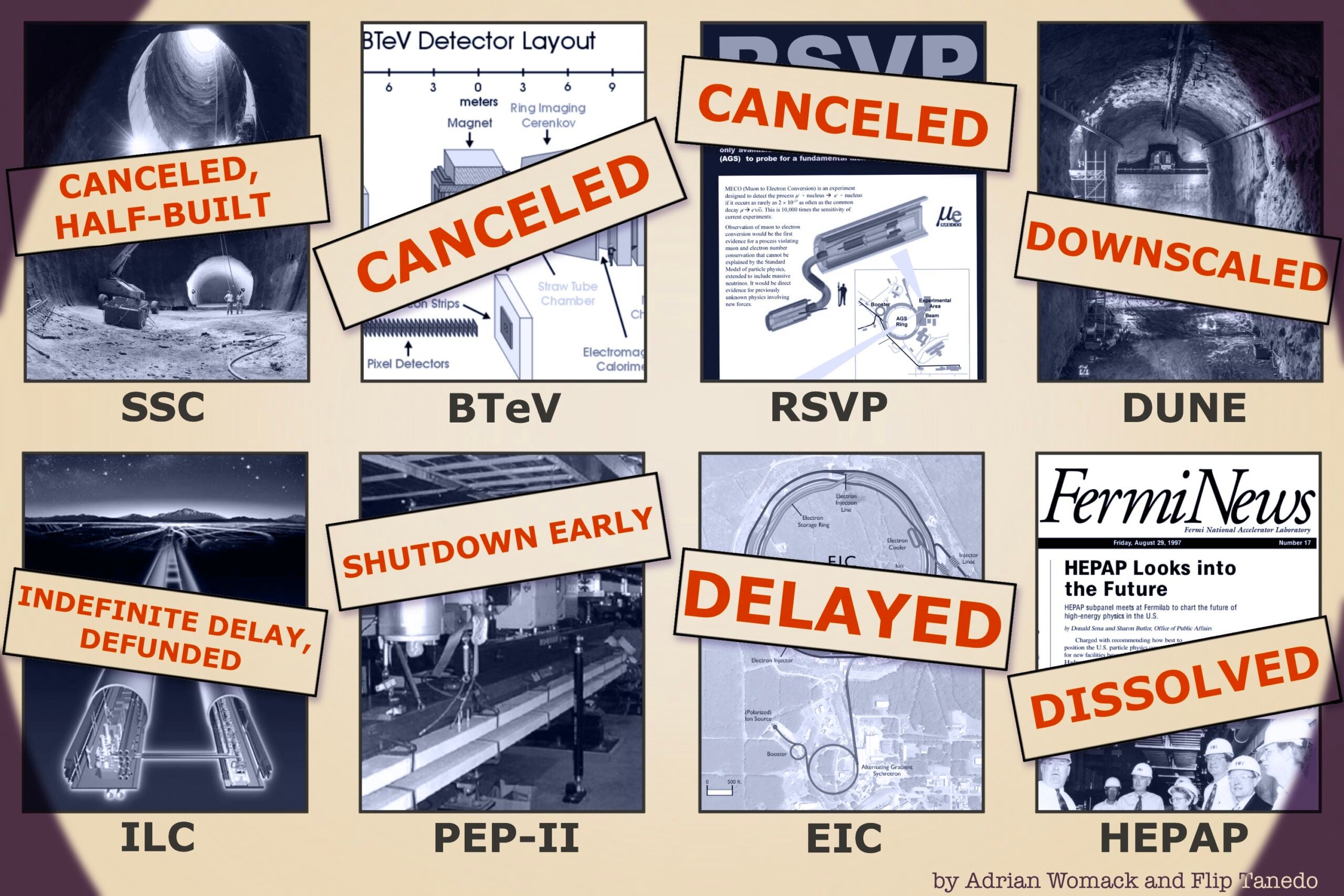

Yet the preeminent role physics played in the U.S. grew stale in the 1990s amid Congress’ focus on balanced budgets. The watershed moment came in 1993, when lawmakers cancelled the Superconducting Super Collider, a half-built machine that would have discovered the Higgs boson two decades before Europe’s Large Hadron Collider did. Had Congress continued to fund the Superconducting Super Collider, the Nobel-Prize winning discovery would have been made in the U.S. a decade earlier.

Faced with budget austerity, the U.S. has become an unreliable partner on high-impact, large-investment projects. In 2008 we reneged on commitments to the would-be International Linear Collider and ITER, an international nuclear fusion experiment. In more recent years, cost overruns in our smaller-scale flagship project, DUNE, consume other parts of the science budget.

How the U.S. funds science is a big part of the problem.

In contrast to the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), which is funded by a treaty obligation from its member states, U.S. science depends on the annual whims of Congress. Every year, the congressional appropriations committees choose whether or not to continue funding for a program.

This budgetary arrangement is supposed to be a way to build in project accountability; instead, it has made large projects a political football. Planning major transformative projects is impossible when our federal science agencies can’t even rely on keeping the lights on.

But money isn’t the only problem.

The future of science relies on support for basic research and a culture and environment that builds up people.

Because particle physics builds and operates large-scale facilities, our community prepares decadal studies to determine future scientific priorities. Until recently, information from these studies fed into a federal advisory committee called the High-Energy Physics Advisory Panel (HEPAP), which provided guidance for the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation. HEPAP allowed physicists to debate the merits of plans for the next twenty years.

I served on this committee until October 2025, when we were shocked to receive “thank you for your service” emails informing us that HEPAP — along with five other science advisory groups — would be disbanded and diluted into a single science advisory committee representing science and industry.

Shortly afterward, the Trump administration announced its Genesis Mission, a national AI platform that few, if any, scientists asked for, but that many quietly worry is a way to dole out large contracts to the tech industry while also giving away national laboratories’ computing resources and datasets for AI training.

How to Restore the U.S. as a Leader in Science

It is no coincidence that Boeing’s ascendance went hand-in-hand with the rapid growth of the University of Washington and the Lakeside School (filled with Boeing families) that nurtured Bill Gates and helped turn Seattle into an engineering city.

In the same way, the science done at universities and labs across the country has been a beacon to recruit worldwide talent and a cradle for the future scientists, engineers, thinkers, and entrepreneurs who have pioneered U.S. economic dominance.

The future of science relies on support for basic research and a culture and environment that builds up people. Boeing has started to rediscover this lesson by bringing formerly outsourced production back to Seattle so engineers who make parts may work side by side with those who put them together.

For U.S. physics to do the same, a first step would be to ensure that the Department of Energy’s all-in-one science advisory committee commits to regularly convene subject-specific subcommittees — as HEPAP did for its decadal study — to ensure that our physics priorities are identified by physicists, not politicians.

The bigger, tougher step is to ensure that large projects have a pathway for reliable, long-term funding that is insulated from political budget wrangling. While reduced funding simply means less output for most fields, paying for half of a collider nets you the same scientific production as no collider at all. And unexpected appropriations cuts lead to project delays, which only make the project more expensive.

Congress needs new funding structures with legally binding, long-term funding while also having well-defined guardrails for cost overruns. Limiting Congress’ ability to pull back appropriations for approved projects would be a bold but necessary step to ever have the capacity to build great civilian science projects.

Before its demise, one of the last things HEPAP approved was an ambitious, long-term vision for science: a muon collider. Unlike next-generation particle collider proposals from Europe and China, a muon collider would be a next-next-generation machine that would answer questions about our place in the universe and would build the technological advances of the 22nd century. Our last collider, the Tevatron, in Batavia, Illinois, was built in 1983. Most of the scientists and engineers who built it are now retired.

Building the muon collider is a tremendous challenge and would require urgent research and development to draw on the last generation’s hard-earned expertise. The alternative would be to cede our country’s capacity to dream big.