The first Space Age dawned with the launch of Sputnik 1 on October 4, 1957. It was, of course, an unprecedented era of spaceflight, but it was also something more: a half-century in which a handful of governments used space achievements — especially crewed missions and robotic journeys to other planets —– to signal the superiority of their economic and political systems.

Now, many speak of a new Space Age, or, as some put it, a NewSpace Age. It’s a second chapter in the story of humanity’s expansion beyond Earth, a chapter written not only by the old powers —– primarily the United States and Russia —– but also by a host of new space agencies, and most importantly space corporations, with the ambitions and resources of governments.

How Spaceflight Became Corporate

The private sector has long been part of spaceflight in capitalist economies. In the 1960s, NASA’s Apollo program, for example, coordinated the labor of some 300,000 people in 20,000 industrial firms. The military and intelligence wings of the U.S. space effort also depend on large defense contractors. But these firms haven’t been independent operators in outer space.

The first Space Age was not just an era of spaceflight, but a half-century in which governments used space achievements to signal the superiority of their political and economic systems.

What changed? The history of the dominant player in the NewSpace Age —– Elon Musk’s SpaceX —– answers the question.

By the 1990s, innovation had stagnated across the U.S. aerospace agency, while the cost of lifting payload into outer space was prohibitively high. There were three big reasons. First, the Space Shuttle, which was supposed to enable routine and low-cost access to outer space, turned out to be dangerous, labor-intensive, and very expensive.

Second, NASA and the U.S. Department of Defense relied on cost-plus contracts that reimbursed aerospace firms for the costs of launching a payload into orbit and gave them a guaranteed profit margin. Cost-plus contracts made sense early in the first Space Age, when technologies were genuinely unprecedented and failure would have catastrophic political consequences, but by the 1990s they created a climate of risk aversion in the aerospace industry.

Third, the contraction of the industry after the Cold War forced firms to merge, further stifling their incentive to innovate.

The rise of Silicon Valley, however, created new wealth —– and new technologies that seemed capable of allowing rockets to land autonomously. Rockets that could land themselves could be used again, driving down launch costs.

When Musk made his first fortune with an online payment platform, he saw an opening to disrupt the aerospace industry. He founded a new company, SpaceX, that would grow by leaps and bounds after NASA cancelled its Space Shuttle program. In anticipation, NASA created a new payments system that spurred the commercialization of spaceflight by incentivizing companies to develop novel ways of getting astronauts into orbit. SpaceX was the biggest beneficiary.

The wealthy founders of NewSpace industries were —– and are —– an odd bunch. As tech enthusiasts, they grew up with the science fiction of Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Lester del Rey, Arthur C. Clarke, and other authors from the so-called Golden Age of American science fiction. Science fiction from this era was full of engineer-heroes, technologies that reshaped societies, and largescale, long-term social engineering.

As both the tech and space industries boomed, and wealth of NewSpace founders ballooned, the ambitions of leading NewSpace companies took on the characteristics of Golden Age science fiction. Musk’s dream for SpaceX, for example, is not just to make human life multiplanetary by settling and terraforming Mars, but more broadly to increase the mass and resilience of humanity.

Two Visions for the Future

Ambitious visions are not inherently problematic. Our species has developed world-shaping powers. Its needs —– for resources, knowledge, and perhaps even energy —– increasingly transcend the boundaries of our finite planet. There is a real need for largescale, visionary planning that charts a sustainable, equitable, and prosperous future for humanity.

Musk imagines a Planet B for humanity: a Mars that steadily grows more habitable through deliberate human intervention.

But not all visions are equal.

Musk imagines a Planet B for humanity: a Mars that steadily grows more habitable, owing to the deliberate transformation of its atmosphere by human settlers. It’s not as crazy as it sounds. SpaceX’s Starship —– a rocket of revolutionary size and reusability —– failed repeatedly in testing, but that was a deliberate part of an iterative design process. Starship is now in advanced development and could ferry settlers to Mars within a decade.

Studies also indicate that the cost of boosting temperatures on Mars may be cheaper than previously believed. The first steps in a planet-altering terraforming project could occur in the not-so-distant future.

But although Mars seems to have been an Earthlike world in its early history, it now seems impossible to terraform the planet into a true second home for humanity. The main reason is that it’s too small. Its diminutive size allowed its core to cool more quickly than Earth’s, freezing the sloshing, superheated iron that once gave it a magnetic field. Without a magnetic field, dangerous solar radiation washed over its surface. Worse, the solar wind began to eat away at its atmosphere. That atmosphere was already escaping because the gravity of Mars was too weak to keep it around. Today, there aren’t enough volatile chemicals —– nitrogen in particular —– to restore the ancient climate of Mars.

Hundreds or even thousands of years from now, it may be possible to introduce new volatiles to Mars by, for example, steering comets into its atmosphere. Needless to say, that’s not possible now. The best that could be done for the foreseeable future is to turn Mars into a world that’s more habitable than it is now, but far less hospitable than Antarctica.

Blue Origin, the burgeoning NewSpace company founded by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, has a very different vision for humanity’s future in space. In this vision, there is no planet B. Earth, with its rich but imperiled web of life, is unique —– and uniquely precious —– in the Solar System, perhaps the cosmos. The purpose of human expansion into outer space should be, first and foremost, to preserve the Earth.

There is no Planet B, not for the foreseeable future, and so the primary purpose of the NewSpace Age should be the conservation of the Earth.

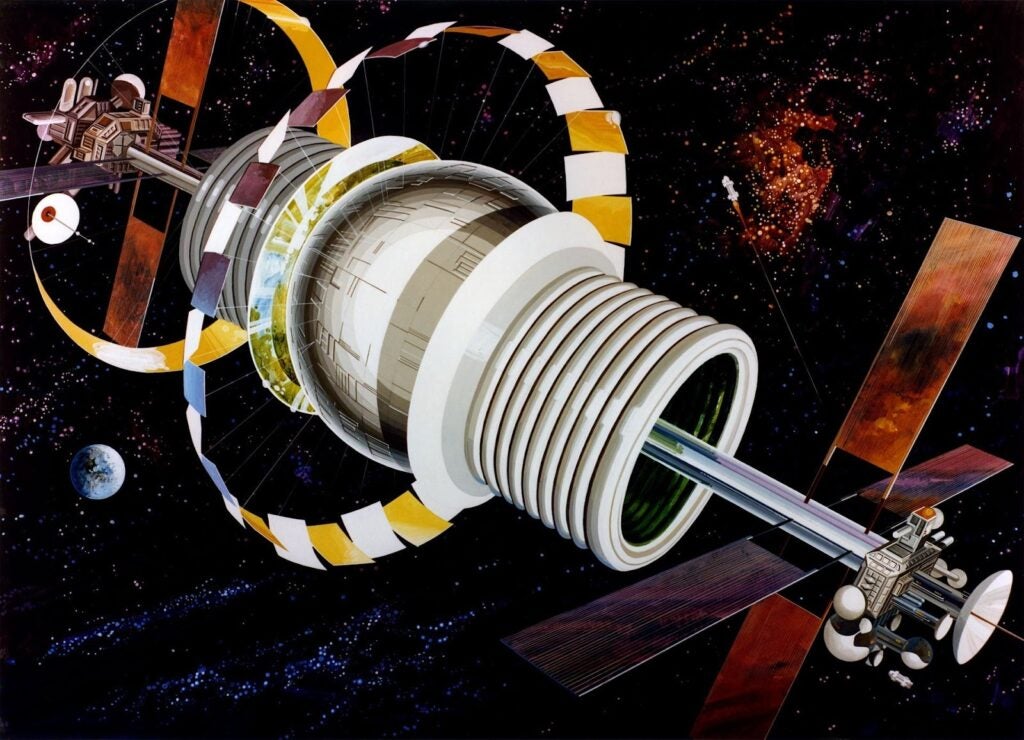

To Blue Origin, the way to do that is to off-world —– to the maximum possible extent —– many of the most destructive activities of humanity on Earth, namely mining, power generation, and perhaps even the construction of new data centers for artificial intelligence. In theory, resources extracted from asteroids could sustain humanity for countless generations, while solar power in space is more efficient than on Earth and could be beamed down to receiving stations. The combination of artificial intelligence with 3D printing could enable large-scale construction projects in Earth’s orbit —– not only power stations or data centers but even, perhaps, a solar shade that directly cools Earth’s climate. In time, space cities could spread out from Earth: giant cylinders that create their own gravity through the centrifugal force of their rotation.

A Bernal Sphere – one vision for a rotating city beyond Earth. Rick Guidice.

In my new book, Ripples on the Cosmic Ocean, I favor the Earth preservation vision for our future. That’s because it respects two essential truths. First, Earth will always be the most habitable planet in the Solar System, even in the wake of a global catastrophe. Second, its web of life —– its biosphere —– has unique and innate value. There is no Planet B, not for the foreseeable future, and so the primary purpose of the NewSpace Age should be the conservation of the Earth.

Of course, there’s another question: Should billionaires really be the ones to forge our future beyond Earth?

For all its faults, the most compelling part of the first Space Age was the idealism that endured despite —– and sometimes because of —– the cynical ways in which superpowers attempted to exploit space achievements. It’s an idealism captured in clichés that still inform how we talk about outer space.

Exploring space, we often say, requires the best of humanity —– the right stuff —– and it ought to be done on behalf of all humankind.

Space settlement is part of many Utopian dreams of humanity’s future, but in these dreams, settlement happens only when humanity has proven itself worthy of being a spacefaring species. In Star Trek, humanity establishes the Federation as it learns to live sustainably on Earth, to eliminate socioeconomic inequality, and to build a genuine democracy.

These days, it feels like a Blade Runner future is a more likely prospect. But the NewSpace Age is young. There’s still time to choose between visions for its future.