Thanks to a Biden-era memorandum, on the last day of 2025, all scientific publications and their supporting data resulting from federally funded research were made immediately and freely accessible to the public. Open access is an important step toward the democratization of scientific research, as it allows everybody — scientists and non-scientists — to avoid paying what has been dubbed a triple-tax on publicly funded research: the cost to develop the study, the cost to assess the quality of the study itself, and the cost to publish the reports.

However, a deeper issue needs to be addressed. Just providing the public with access to the research is not enough; government officials, scientists, and everyday citizens must also build an infrastructure to interpret it. We believe the only way to build a fully democratized and participatory scientific environment is to engage the community in a collective discussion of the meaning and implications of scientific research. Here we focus on our area of expertise, biomedical science, but these concepts apply to all fields.

Just providing the public with access to the research is not enough; government officials, scientists, and everyday citizens must also build an infrastructure to interpret it.

Why Scientific Articles Can Be Hard to Understand

Scientific articles are, for the most part, highly technical reports that can be hard to fully understand if one is not an expert in a specific field. For example, we are both biomedical scientists, but in different areas of specialty — one of us studies inflammation, while the other focuses on the neurobiology of hearing. When we read each others’ work, we don’t immediately grasp the full meaning simply because we are scientists. Scientific articles speak to specialized readers.

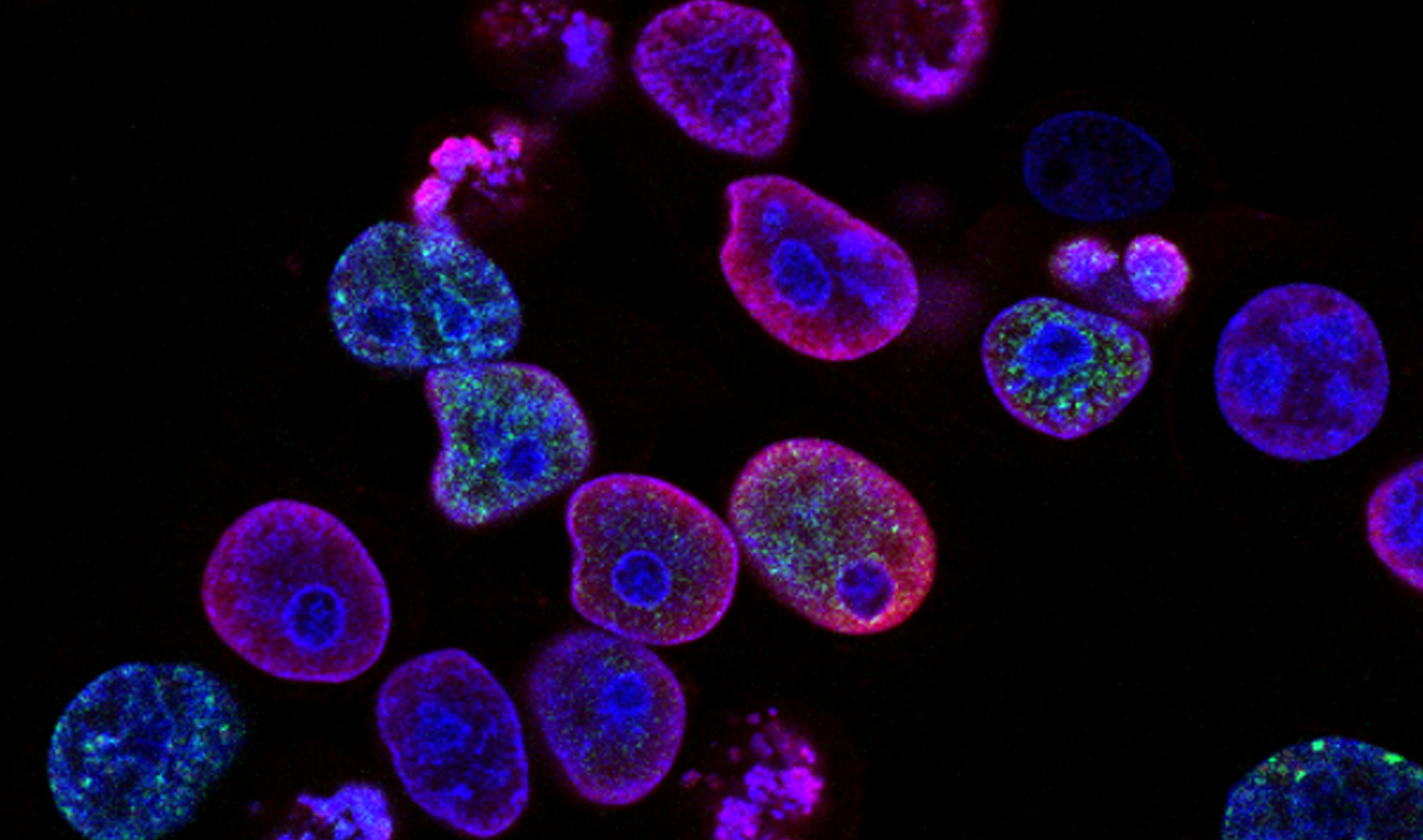

Specialization allows scientists to dig deep into the origins and mechanisms of disease, and specialized language allows scientists to succinctly communicate the results of complex findings. This issue of specialization becomes even more necessary when engaging in and reporting the findings of basic, foundational research — that is to say, studies that do not directly evaluate a potential cause or treatment for a disease but rather examine underlying mechanisms and contributing factors.

Open access to scientific research is like granting free electricity but never building the power lines.

Foundational science is the most challenging to fully grasp for those outside one’s highly specialized field of research, but constitutes the majority of federally funded biomedical research; therefore, foundational science makes up the majority of the studies that have become freely available.

Yet if biomedical scientists are unlikely to be able to parse these studies outside their direct area of expertise, what does it mean for the public at large to have immediate and free access to scientific publications without the infrastructure to interpret them?

Open access to scientific research is like granting free electricity but never building the power lines.

How to Make Good on Open Access

Free access to research results and data as soon as they are published may create opportunities for innovations we could have never imagined because those with a different training or perspective may see these data differently. For example, it could allow patients and their caregivers a front-row seat to the newest discoveries. However, the same scenario could cause lethal errors. In other words, if those discoveries are not interpreted accurately, making publications and data available to the public may lead to misleading health information, which in turn can put people at risk. Disregard for context and inaccurate understanding of a scientific study’s strengths and weaknesses can lead to cherry-picking, which can have devastating consequences.

In addition, research results and data without context risk amplifying mistrust in the biomedical research community. Trust in scientists and medical professionals is already fragile — historical episodes like the syphilis study at Tuskegee and the eugenics movement rightfully discredited the U.S. public health system. Moreover, the dissonance around the evidence demonstrating a lack of causation between vaccinations and autism has caused long-lasting schisms between families, communities, and the public more broadly.

Rebuilding and retaining trust requires that findings should be handled with care. We believe that engaging the community in a collective discussion of the meaning and implications of biomedical research is the only way to proceed toward building a fully democratized and participatory scientific environment — indeed, toward building the power lines to distribute the free electricity.

So how to make good on the promise of open access?

First, many scientists and non-scientists are already working together to tackle very targeted challenges. Two organizations already involved in this process are the Fibromuscular Dysplasia Society of America and SoQuiet: The Misophonia Advocacy Group. We are engaged with these organizations and find them to be great examples of how bringing non-scientists and scientists together to discuss the meaning and implications of research studies can change lives, especially when there is a shortage of answers that can improve patients’ outcomes.

Engaging the community in a collective discussion of the meaning of biomedical research is the only way to proceed toward building a fully democratized scientific environment.

Disease-specific organizations like these provide webinars and other opportunities to discuss scientific results; access to Lived Experience Panels that critique research proposals; and resources such as Registries and Participant Pools, a necessity for disorders that are less prevalent. The impact of patient-involved and even patient-led research can be significant. Long COVID was possibly the first illness where patients organized and published research about their symptoms before any scientists did, pushing the medical community in new directions.

Another model involves community members reviewing research projects before studies are funded. We both have direct experience in this model through the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program. Here, citizen scientists, patients, caregivers and advocates provide the much-needed lived experience perspective, bringing down to earth the pie-in-the-sky schemes dreamed up in the lab.

Who owns science? We all do.

Many communities expect not only to review proposals but also to have a seat at the research table throughout the entire process. Community-based participatory research is an approach in which scholars and community members share ownership of the research from the outset, thereby avoiding a top-down relationship between scientists and the community. This approach is common among studies focusing on the social determinants of health, but could serve as a valuable model for building the infrastructure needed to give real meaning to the concept of free access to scientific output.

In the spirit of democratizing science and sharing ownership of the research we all fund with our taxes, we believe it is essential to collectively devise a solution that serves the needs of both scientists and the broader public. We need that conversation to find a solution that works for all.

Who owns science? We all do.

*Both authors are Public Voices Fellows with The OpEd Project.