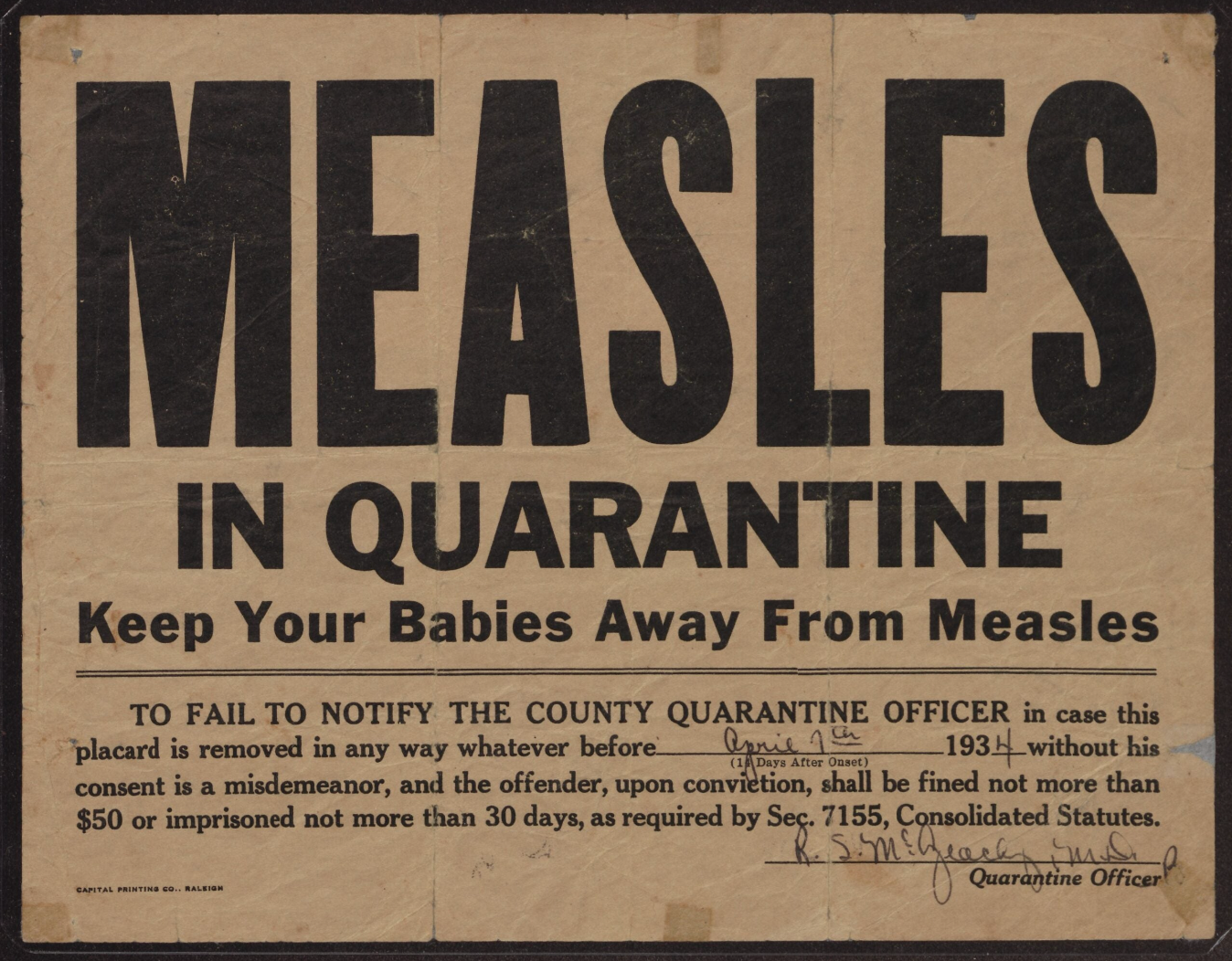

For most Americans living in the latter half of the 20th century, getting vaccinated was an easy decision. Most had first-hand experience with vaccine-preventable diseases including measles, polio, and even smallpox. Americans understood—often from firsthand experience—that vaccination provided a safe alternative to catching those diseases.

By 1980, widespread vaccine uptake enabled the global eradication of smallpox, and led to polio’s elimination in many areas of the world. In 2000, the CDC declared that the United States had eliminated measles as well. That is, high vaccination rates halted the continuous spread of this disease within the nation. Since then, measles cases in the U.S. have remained low, with a few exceptional, localized outbreaks that resulted from measles being imported by travelers from other countries, often in western Europe. Now, however, measles is poised to lose its eliminated status.

Measles is highly contagious and can result in serious consequences including pneumonia, encephalitis, and death. It also erases a body’s immune memory, meaning that people infected with measles become more vulnerable to other pathogens, including ones they may have had before. Economically, widespread measles vaccination is also important. It provides significant financial savings to the country because it keeps people out of hospitals and in school and work.

Measles erases a body’s immune memory, making people more vulnerable to other pathogens.

As anthropologists with thirty-plus years’ experience investigating how people think about vaccines, we have been concerned by new data that show measles vaccination in the U.S. is on the decline and measles on the rise. Our research confirms that decisions against vaccination are not based on lack of education, but instead on lack of trust in science and medicine.

In the past, purposeful non-vaccination in the U.S. was generally relegated to small, self-contained religious communities or to geographically grouped families with specific demographic criteria (wealthy, white, suburban). More recently, however, resistance to vaccination has surged, first during the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequently with the growth of the Make America Health Again (MAHA) political movement.

Decisions against vaccination are not based on lack of education, but on lack of trust in science and medicine.

As direct consequence, measles has come back with vengeance. As of December 31, 2025, there were 2,065 confirmed measles cases, most stemming from 49 outbreaks. Hospitalization occurred for more than one in ten people, about half of whom were five years of age or younger at the time. Three have died. Most of the people who contracted measles (92%) were unvaccinated and others (7%) had only received one of the two recommended measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine doses.

The high rate of measles in the U.S. in 2025 is the direct result of non-vaccination. In Texas, for example, the initial and most widespread outbreak of measles appeared in January in a Mennonite community, where vaccination was historically less common due to cultural reasons. So, in typical years, the virus was contained within that community. But in 2025 the disease spread to other communities with low vaccination rates: communities where non-vaccination was a new phenomenon linked to MAHA-related medical mistrust. By mid-April, ten outbreaks in twelve different states had been reported and outbreaks continued to increase as the year wore on. Now, the U.S. is very close to losing its ‘eliminated’ status for measles.

The high rate of measles in the U.S. in 2025 is the direct result of non-vaccination.

MAHA-related medical mistrust is supported by how the current Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has approached the measles outbreaks and vaccination writ large. Instead of advocating for vaccination, Kennedy—who has long downplayed the benefits of vaccination to further his political standing—urged parents to “do your own research.” This, in turn, has both fueled conspiratorial thinking and sparked confusion in the highly polarized cultural environment in the US, muddying the waters for many parents in the process of deciding on vaccines for their children.

Catalyzed by this high-level endorsement, what was once a fringe and minimal problem, often termed ‘vaccine hesitancy,’ is today of paramount public health concern.

Yet, what we’ve seen is that people’s immediate concerns—such as social belonging and whether children in the community are contracting vaccine preventable diseases—can, when harnessed, be more important drivers of parental decision-making than political messaging. Ultimately, most parents make whatever choice they believe will best support their children’s health and well-being.

Historic Cultural Shifts in Immunization

This is not the first time vaccines have been politicized in the United States. The pattern of weaponizing vaccination for social and political aims is well-worn. Objections have long been culturally and socio-politically grounded, often justified with reference to powerful personalities; and the scientific value of vaccination has served for equally long as a useful tool in competitions over power and authority.

As one example, when smallpox inoculation—the risky precursor to modern vaccination—was first introduced to Boston in 1721, it led to heated debates, an attempted bombing, and death threats.

Many physicians and political leaders at the time stood against vaccination. Adam Winthrop wrote, “I should have less distress in burying many children by the absolute acts of God’s own providence [i.e., naturally acquired smallpox] than in being the means of burying one by my own act and deed.”

Yet, many members of the clergy supported vaccination. Reverend William Cooper countered “If God shows us the way to escape the extremity and destruction… should we not accept this gift with adoring thankfulness?”

In Europe, where inoculation was also a new practice, the opposite situation existed. Vaccination was largely rejected by members of the clergy but widely accepted by the medical establishment and political elites at the time. Each argued its position attempting to shore up their claims to expertise and authority.

After the 1721 epidemic, despite evidence that fewer people died from inoculations than from naturally acquired smallpox infections, the controversy remained. Many questioned: Would the people who died after being inoculated against smallpox have died from the actual disease? Would they have contracted smallpox in the first place? And what about those that died from the disease, would they have died if they had been inoculated?

The last question was one that likely troubled many individuals, particularly parents. Benjamin Franklin’s son Francis died from smallpox during an outbreak in Boston in 1736. He later wrote “I long regretted bitterly and still regret that I had not given it to him by inoculation.”

Vaccination Controversies: The Science

When an individual is vaccinated, they are exposed to a version of the pathogen that has been altered so that it does not produce disease but still contains the antigens that stimulate the body’s immune response. If a person is later exposed to the authentic disease-causing organism they were vaccinated against, their immune system will respond quickly and efficiently. Research on the MMR vaccine, for instance, has shown that vaccinated persons are 35 times less likely to contract measles than unvaccinated persons.

Despite the individual benefits, the true power of vaccination is in its widespread uptake. When a sufficient proportion of a population is immune to a disease—as occurs through widespread vaccination—herd or community immunity is achieved. This means that, given random mixing of individuals within the population, if a disease-causing pathogen is introduced, it cannot spread. In other words, people who are immunocompromised or unable to be vaccinated for another reason, will be protected by the immunity of their community.

To ensure widespread vaccine uptake capable of maintaining community immunity, vaccination is often mandated by law. While no federal policy exists in the US, every state except Florida—which only recently repealed its vaccine mandates—has laws that require vaccinations for children attending day care and school. And until recently, most people conformed.

Why have we observed such a rapid dissolution in vaccine confidence? While modern vaccines are unarguably safer than smallpox inoculations of the 18th century, an increasing number of people in the U.S. consider vaccines controversial because, although existing research has shown that vaccination is safe and extremely effective, they are not without risk. Risks range from minor side effects, such as redness and soreness around injection sites, to extremely uncommon but severe side effects including seizures and brain damage. For the MMR vaccine, as an example, one in one million individuals experiences an allergic reaction that can result in seizures, brain damage and/or death.

Concerns about vaccines don’t end with the accepted risks, however. In many ways, unproven risks have profound consequences. Andrew Wakefield’s since redacted paper in The Lancet incorrectly concluded that the MMR vaccine was associated with autism. Despite the journal’s retraction, and regardless of multiple scientific studies showing no association between vaccination and autism, the controversy lives on. Indeed, it has been arguably the singular most powerful factor in driving vaccination misinformation, fear, and anti-vaccine activism in recent times particularly in the MAHA movement where vaccination is once again being leveraged for political gain.

Disease will Drive Demand

In all probability, as vaccine-preventable outbreaks of diseases like measles spread, and news of measles’ potential loss of its status as ‘eradicated’ filters out, parents will be more motivated to shift their views on vaccination once again. News of the measles outbreak in Texas, for example, was followed by increased demand for MMR vaccination. The South Plains region, home to the original outbreak, saw a 60% uptick in vaccination compared to 2024. Heightened awareness of the debilitating and sometimes tragic outcomes of measles infections even led some parents to request vaccinations early for their children, and demand for both adult and pediatric doses was so high that some pharmacies and doctors’ offices experienced shortages.

Similarly, when an outbreak began in a temporary shelter for migrants in Chicago in 2024, the immediate concerns of those who had potentially been exposed underwrote a vaccination surge. Demand was supported by active case-finding and a coordinated mass vaccination campaign at the shelter. More than eight hundred residents were vaccinated over the course of three days. In these cases, addressing access positively affected the outcome. Yet, people’s initial impulse to vaccinate came after seeing how devastating illness could be.

And in 2018-19, when the largest measles outbreak since 1992 occurred in the Orthodox Jewish community in New York City (NYC), demand for vaccination skyrocketed. NYC’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene assisted in the vaccination efforts. In Williamsburg alone, which was the epidemic’s center, vaccine acceptance increased in the community from just under 80% to 91%. This increase was just enough, in this case, to support community immunity.

These examples showcase how the goal of keeping ourselves and our loved ones safe from vaccine preventable diseases is at the root of individual vaccine choice-making—at least when such diseases are truly a threat. When other people’s children or those in one’s community are dying from vaccine preventable diseases, vaccinating becomes the obvious choice.

It might be nice to turn back the clock to a time when leaders across the political spectrum robustly supported vaccination, but this is unlikely. We must instead face the current reality that more outbreaks must (and will) emerge before, under the weight of tragic disease-related losses that could have been prevented, public opinion, regardless of political machinations, swings dramatically back in favor of widespread vaccination.

When vaccine-preventable diseases become a real and visible threat, vaccinating becomes the obvious choice.

In the interim, continuing to shine a light, within affected communities and beyond, of the costs of skipping vaccines—through accurate public health information and statistics—is crucial. So is fully funding vaccine programs that provide access to communities in need. While the politicians fight, given ample, publicly visible, persistent support from scientists, journalists, policymakers, and everyday vaccine advocates these data—and the palpable suffering behind them—still stand a chance to show families the way.