The most important story in the world may be unfolding in the Atlantic Ocean.

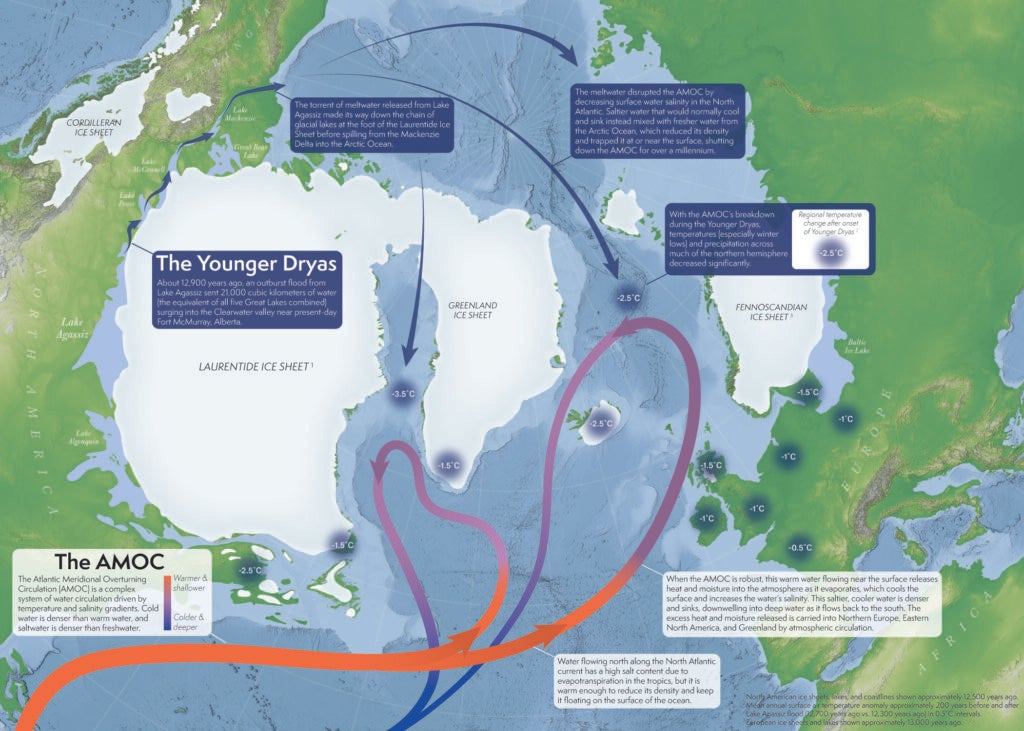

There, an immense system of currents, collectively known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, moves warm, salty water north towards the Arctic, and pushes cold, relatively fresh water south to the equator.

Because the world is warming, the AMOC seems to be weakening. Now, a growing body of evidence indicates that it is approaching a critical threshold. If it passes that threshold, it will begin to shut down.

As a historian of climate change, I know that the consequences of an AMOC slowdown, let alone a collapse, could be catastrophic. That’s because it’s happened before. Careful study of cores drilled from ice sheets and seabed sediments has shown that, over the past 60,000 years, the AMOC collapsed at least seven times. In each case, warming seems to have been a trigger.

Before the most recent AMOC collapse, the world was much colder than it is now. Glaciers covered much of North America and Europe. But in summers, cycles in the tilt and wobble of Earth’s rotation had started to bring a little more sunlight to the northern hemisphere. Temperatures warmed just enough to trigger changes in sea ice and wind patterns that pulled up carbon dioxide from the deep ocean. The warming accelerated and glaciers began to melt, creating enormous lakes.

About 12,900 years ago, the glacier bordering the biggest lake, named Agassiz, seems to have crumbled. Most of the lake’s water surged into the Atlantic Ocean.

The freshwater influx threatened Atlantic Ocean circulation, but to understand why, you need to know how the AMOC works. In the steamy tropics, evaporation makes ocean water extra salty, or saline. Warm, tropical water cools down as it migrates north. Because it stays salty, it’s denser than the water that surrounds it. In the North Atlantic, the salty water sinks into the deep ocean.

This is the engine that keeps the AMOC going: the salinity of cooling water from the tropics. It’s also why the AMOC is vulnerable to global warming. Rising temperatures can cause the water to stay warm. Melting glaciers can lead it to mingle with freshwater, lowering its salinity.

That’s exactly what seems to have happened when the waters of Lake Agassiz spilled into the Atlantic. Because the AMOC moves heat north from the equator, temperatures plunged across the northern hemisphere. In some regions, they dropped by more than ten degrees Celsius in a matter of decades.

The cooling lasted some 1,200 years. It’s called the Younger Dryas, after Dryas octopetala, a little white flower that thrives on the frigid tundra. The first evidence for the Younger Dryas came from pollen deposits that registered the presence of the flower in areas that are now relatively warm and forested.

Our distant, hunting and gathering ancestors struggled to survive the Younger Dryas.

In northern Europe, for example, populations distinguished by their flint blades — known as the Federmesser — seem to have abandoned hunting grounds that were suddenly too cold to live in. On the other side of the Atlantic, hunters armed with “Clovis points,” a kind of fluted projectile, followed the migration of caribou and other big prey into expanding tundra environments.

It was this capacity for mobility that had long allowed small bands of hunting and gathering humans to endure staggering changes in temperature and precipitation. In fact, some communities may have actually benefitted from cooling and drying trends. Populations in the nearby Ahrensburg culture, named after a valley near a German town, learned to gather for mass hunts of big animals that thrived in the tundra spreading across central Europe.

But by the onset of the Younger Dryas, one community — the Natufians of the Levant — had started to live more like we do today. Some archaeologists have argued that Natufian populations grew in the leadup to the Younger Dryas, as warm, wet weather nourished ecosystems in the Levant. When the climate suddenly cooled and dried, those populations were too big and sedentary to migrate. They may have been among the first to experiment with agriculture — to generate food that could no longer easily be gathered.

New evidence suggests that the Natufian development of agriculture unfolded after the Younger Dryas. But if it didn’t, that would be a strange irony. We may be more vulnerable to an AMOC breakdown than our distant ancestors precisely because humanity’s enormous population now depends on vast but precarious systems of agricultural production in a handful of maize, rice, and wheat-growing regions. Human communities have lost their capacity to migrate in pursuit of their food, once our most powerful tool in the face of climate change.

What’s more, an AMOC breakdown today would look different from those of the past, because human greenhouse gas emissions have made the world much warmer — warmer, perhaps, than it has been in tens of thousands of years.

We may be more vulnerable to an AMOC breakdown than our distant ancestors precisely because humanity’s enormous population now depends on vast but precarious systems of agricultural production.

If greenhouse gas emissions persist at high levels, European summers could be hotter than they are now even after the AMOC shuts down. But winters would be far colder. That’s because, in the North Atlantic, winds blow predominantly from the west. As they blow over the warm water that the AMOC pushes north, they gather that warmth and deliver it to Europe. This effect is strongest in the winter, when the Sun provides little direct heat. It’s why Europe has mild winters, relative to North America at the same latitude.

If the AMOC breaks down, winter temperatures across Europe could plummet by several degrees Celsius. In some computer simulations, cold waves with temperatures of about -20 °C become possible in London, and -48 °C in Scandinavia. At the same time, the summer heatwaves that have swept across Europe in recent years could actually get worse. Storms could also intensify, because an enormous divide would open between temperatures in northern and southern Europe.

But the worst consequences of an AMOC shutdown could affect life-giving monsoon systems in Africa and Asia.

The strength of these systems depends on temperature differences between latitudes, and between land and water. Evidence for past climate change and simulations of the future both indicate that an AMOC collapse will scramble these differences, shifting and weakening monsoon systems. Droughts would be routine and severe across South Asia and Central America.

The United States could be spared from the worst temperature and precipitation impacts of an AMOC breakdown. But warm water that once flowed north would now pool along the east coast. That would cause a damaging regional spike in sea levels.

The scale of human suffering that could be unleashed by an AMOC collapse is hard to fathom. Simulations suggest that if the world warms by only one degree Celsius more than it already has, an AMOC shutdown could more than halve the amount of land that is today highly suitable for maize and wheat production. Millions — perhaps billions — could be in peril.

Simulations suggest that if the world warms by only one degree Celsius more than it already has, an AMOC shutdown could more than halve the amount of land suitable for maize and wheat production.

Scientists used to believe that an AMOC breakdown would be unlikely to happen in the coming century. Unfortunately, new measurements taken by everything from satellites to floating robots indicate that the AMOC is already slowing down. Worse, climate models now simulate a catastrophic AMOC weakening in realistic scenarios of twenty-first century warming.

The tipping point could be reached in the next decade, when the formerly cold, salty water stops sinking as deeply. Once that happens, the northern AMOC would slide irreversibly towards an eventual collapse. And just like in the Younger Dryas, it would take many centuries to recover.

The best way to stop this tipping point from happening is to slash greenhouse gas emissions and slow the rate of global warming. Doing so will mean reversing the current campaign in the U.S. against solar and wind power. It will mean expanding electric vehicle subsidies, rather than cutting them.

But reducing greenhouse gas emissions may not be enough. Simulations indicate that there would be a low but very real risk of an AMOC collapse even in a world that’s scarcely warmer than it is now.

Governments must therefore learn from the communities that survived the Younger Dryas. Today’s populations cannot move to greener pastures, but they can develop ways of producing food that are less sensitive to climate change. Governments should cooperate to develop ways of buffering food shocks and sustaining agricultural production in short, erratic growing seasons.

Support could mean a dramatic expansion of strategic grain reserves. It could entail major investments in climate-controlled agriculture, from high tech greenhouses to vertical farms. It could also involve intensifying efforts to develop genetically modified crops that grow quickly and resist drought or temperature extremes. Such preparations would have the added benefit of protecting populations from other climate shocks, from a surge in global warming to nuclear winter.

It is a dangerous world, and many problems may seem more urgent than a little-known system of ocean currents. The perception that other priorities loom larger could be an illusion.