The first quarter of the 21st century was an anomaly. The tragedy of the AIDS epidemic and other crises led to a golden age of global health assistance, defined by a massive influx of resources and a shift of health from the margins of foreign policy to its center. Development assistance grew fivefold, from $7.7 billion in 1990 to more than $40 billion by 2019.

The results were extraordinary. PEPFAR and The Global Fund transformed HIV from a death sentence to a manageable condition, saving more than 25 million lives. Malaria deaths were nearly halved. Gavi supported vaccination of hundreds of millions of children and prevented tens of millions of deaths.

But this success was built on a foundation of external primacy. Because the money came from the outside, donors drove the agenda. Nevertheless, we operated under an unshakeable, but ultimately false, assumption: That this level of support would continue indefinitely.

The first quarter of the 21st century was an anomaly — a golden age of global health built on the false assumption that external support would last forever.

That era is over. Funding is contracting sharply across the board while simultaneously shifting in form, priorities, and modalities. This is not just a change from the United States but also from other major donors, including the United Kingdom, Germany, and France. Geopolitical trust has frayed. The old model no longer fits our world.

The question now is whether we define the next era deliberately … or allow drift and damage to define it for us. In my book, The Formula for Better Health: How to Save Millions of Lives – Including Your Own, I argue that progress requires three things: see problems clearly, believe that what seems inevitable can be changed, and create practical systems that succeed at scale.

See: The Human Cost of the Lethal Gap

Seeing begins with an uncomfortable truth: In public health, fiscal choices are life-and-death decisions. Politicians and budget officials sanitize funding cuts as technical adjustments or cutting waste. They are not. They are the direct cause of deaths from untreated malaria, interrupted tuberculosis care, and sluggish outbreak responses.

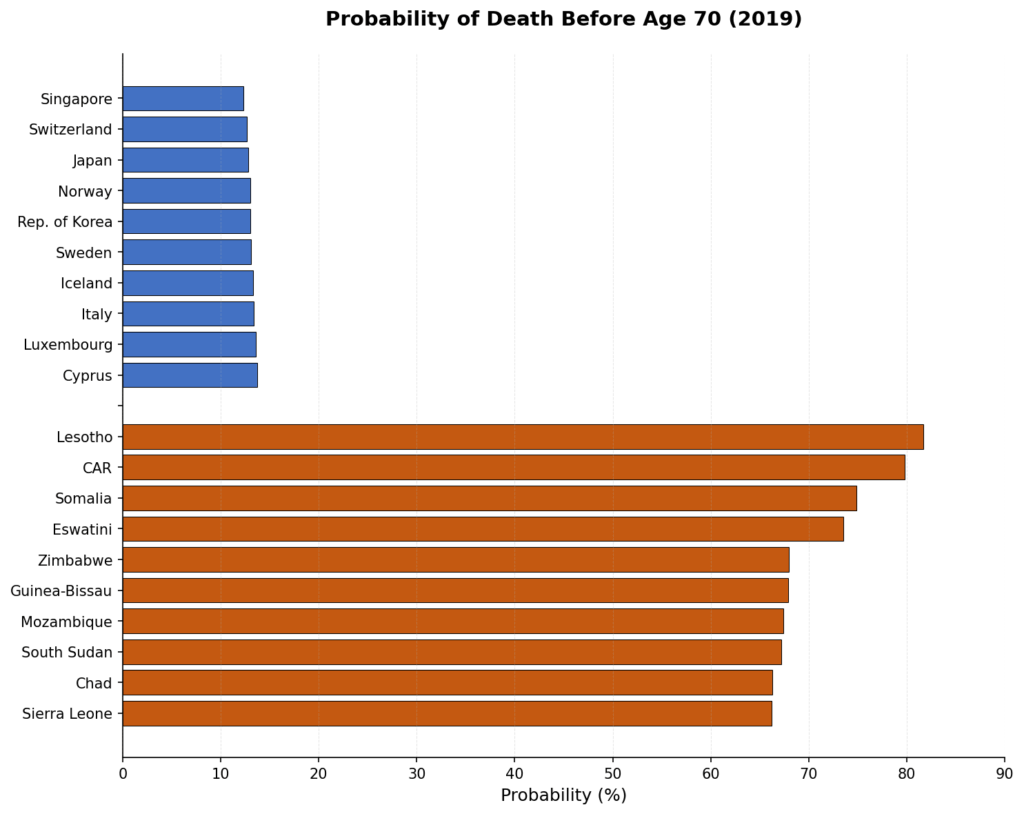

We can break this silence by focusing on a single, unsparing metric: minimizing deaths among people under 70. This metric is an ultimate measure of a society’s health.

The lethal gap is stark: In the healthiest countries, the chance of dying before age 70 is below 15 percent, whereas in the least healthy countries it exceeds two-thirds — a fivefold difference in the odds of premature death (see chart).

In public health, fiscal choices are life-and-death decisions — funding cuts are the direct cause of preventable deaths.

The U.S. sits well outside the top tier, at roughly a 24 percent risk — nearly double that of the best performers and surpassed by Costa Rica, Thailand, and Vietnam, which have much lower incomes than the U.S. but it’s people are healthier and live longer through stronger prevention, primary care, and public health.

Believe: Progress Is a Choice

Belief isn’t just about optimism; it’s also about momentum. The most dangerous mistake we can make is assuming that failure is inevitable.

Cynicism ignores the fact that the tools at our disposal are expanding even as budgets shrink. Wastewater surveillance that can detect an outbreak before clinical cases appear, hypertension medications that cost less than a penny a day, and AI-driven digital systems can improve information and program management to create faster, more efficient systems.

These tools make progress more achievable than ever, but they accomplish nothing without a systematic approach to create a healthier future.

Create: The Architecture of Productive Interdependence

To move from external primacy to productive interdependence, we must recognize that global health is not a zero-sum game but a win-win for the world. Nations may compete economically, but health is a unique arena where the success of one benefits all.

In the progression of development, we move from dependence to independence, and finally to interdependence — countries do not just help one another out of obligation but because our collective health is inextricably linked. Productive interdependence is the recognition that when one nation successfully stops an epidemic or innovates a better way to protect or improve health, every other nation becomes safer and stronger.

Public health is, like politics, the art of the possible.

Productive independence requires four disciplined steps.

First, prioritize. We must reject the myth that it’s possible to do everything for everyone. Countries must set their own priorities based on evidence of what will actually reduce deaths of people under 70. Without a clear choice of what matters most, nothing will be achieved at scale.

Second, simplify. Complex systems and programs don’t scale. If a system is too complex for a community health worker to manage in a rural village or informal urban settlement, it isn’t a solution.

Third, communicate. This starts with listening. We must understand how communities perceive their own health risks then find the right messages and messengers. Effective communication builds the public support necessary for sustained investment.

Finally, we must systematically overcome barriers. Progress requires understanding the political economy — knowing who wins and who loses from change and building coalitions strong enough to overcome resistance.

Making Primary Care Primary

For nearly fifty years, since the Alma-Ata conference of 1978 that established primary health care as the essential foundation for global health, we have called for better primary health care and largely failed to deliver it. To change this dynamic, primary care must actually be primary.

Primary care is the first and most frequent point of contact between a person and the health system, providing essential prevention and treatment where people live and work. Making it primary requires a fundamental shift so primary care is funded sufficiently and receives high priority for both staffing and resources.

This transition happens by strengthening the groups that can demand and achieve it. We must empower the forces within government — specifically health ministries and primary care units — to prioritize these services while building coalitions of patient groups, community organizations, and health workers to demand improvement.

When these two forces of government capacity and community demand align, they create a virtuous cycle. As primary care systems deliver better care, they earn greater public trust, which in turn builds the public and political support necessary for increased and sustained investment.

The Next Era

The success of the next quarter-century should not be measured by the volume of capital flowing across borders but by whether we greatly reduce deaths of those under 70. (Doing so will also reduce death and disability at all ages.)

If we see clearly, believe progress is possible, and create systems of true productive interdependence, the next era of global health will be defined by progress that is not only faster, but longer lasting.